The small island is located near Bluffton, South Carolina between Port Royal Sound, SC and Savannah, Georgia. It is in the Colleton River near an important archaeological zone, which last functioned as the Capital of the Yamasee Confederacy (Native Americans). However, for many centuries before then, it was occupied by a branch of the Creek Peoples, most people associate with the Altamaha River in Georgia.

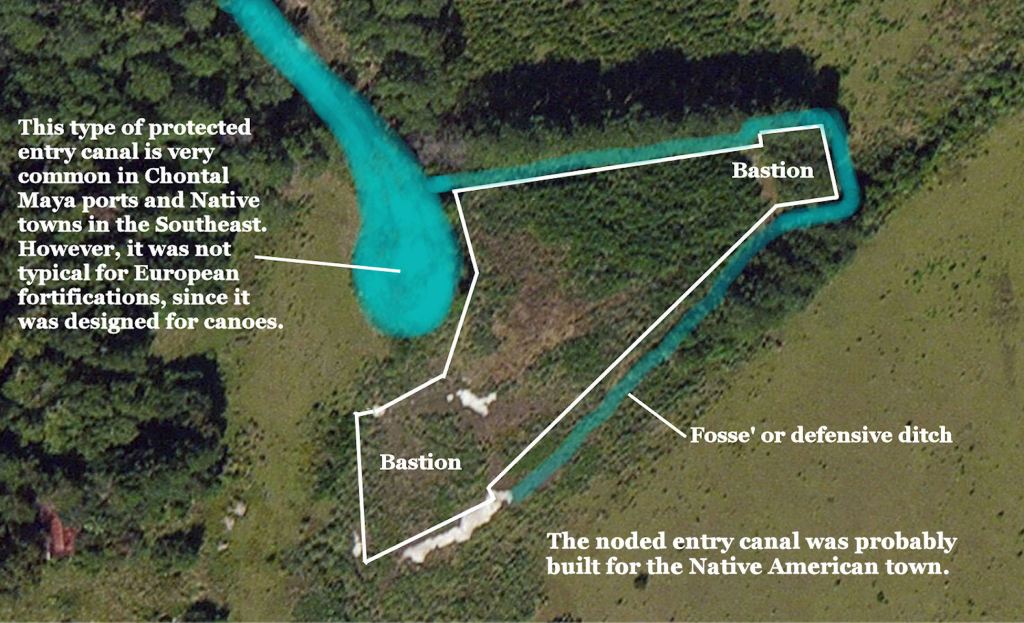

Yet, it has features similar to the ports built by the Chontal Mayas along the Gulf Coast of Mexico, but also features similar to a type of fort, built by the Spanish in the Late 1500s on the South Carolina coast and in the Philippine Islands. Perhaps, it is “All of the above?”

by Richard L. Thornton, Architect & City Planner

A subscriber to The Americas Revealed, who renowned for his “ghost tours” of Savannah, GA, contacted me recently with a request. He wanted to start giving tours of Native American and Early Colonial heritage sites in the Savannah Area, but didn’t know where they were. While cooking dinner the other day, I was glancing at the new USGS LIDAR scan for the Parris Island, SC area . . . looking for both mounds and European forts, then noticed this island. It is across the Colleton River from a definite archaeological zone, the site of Altamaha Town.

Altamaha Town was founded possibly as early as 1695 AD by a band of the Yamasee Confederacy. However, the site had been occupied repeatedly by other peoples, going back to at least 1500 BC. The Yamasee It was occupied the locale for about 30 years. The Yamasee village consisted of dispersed farmstead compounds, not a compact village. Typical of Tabasco and southern Vera Cruz States, Mexico, each extended family cluster had its own raised bed gardens, called “yamas” in that part of Mexico. The Altamaha Town site contains two burial mounds, which predate the arrival of the Yamasee. The Altamaha Town site was partially excavated during the 1980s, by an archaeological team, led by Chester B. De Pratter of the University of South Carolina.

The Native Americans in this part of the South Carolina Coast called themselves the Okate or Oka-ni, when British settlers arrived in the 1670s. They were a branch of the Creek Indians. The primary province of the Okate was within the Oconee River Basin in Northeast Georgia. There was also a few Okate villages in extreme Northwest South Carolina in Oconee County. They were NOT a Cherokee tribe, as stated in several South Carolina sources.

Etymology

Both South Carolina academicians and online references got the meanings of words way wrong. Their meanings are highly significant for understanding the Southeast’s true past.

- Tama is the Totonac, Itza Maya, Western Maya, Chontal Maya and Itsate (Eastern Creek) noun and verb for “trade.” Contemporary Muskogee-Creek speakers in Oklahoma do not know this usage of the word. In Muskogee, tama is the word for a drum. It is also the Japanese word for a drum.

- Altamaha is a Chontal Maya place name, which can be interpreted as either Al Tama Ahaw (Place of the Trade Lord) or Al Tama Haw (Place of Trade – River).

- Okate means “Water-People” in Itsate (Eastern) Creek and some Chontal Maya dialects.

- Okani (Oconee) means “Water-Born in” in the language spoken by the Okate. The Okate believed that after migrating by canoe from the south, they lived on islands in the Okefenokee Swamp and became a distinct ethnic group there.

- Yama is an isolated agricultural field created by slash and burn methods in southern Vera Cruz, western Tabasco and formerly in the Southeastern Coastal Plain. The equivalent word in Eastern and Yucatec Maya is milpa. It appears to have also been the name of the a province and an ethnic group in southern Vera Cruz. The Yamapo River flows across that region from the slopes of the the Orizaba Volcano to the Gulf of Mexico. It is the “Bloody River,” mentioned in the Kaushete-Creek Migration Legend.

- Yama was also the name used by the Creeks for the Native American people living along the Mobile River in present-day Alabama.

- Yamasi means “Yama – descendants of or colony of” in both Muskogee Creek and Itsate Creek.

- Cusabo is the Anglicization of the Panoan word, Kaushebo, which means “Strong or elite – Place of.” The Panoans are concentrated in Eastern Peru.

*From Okatie, SC to Tybee Island, GA, the Native American Place Names are Itza Maya. North and south of that corridor, the Native American place names are of South American or Caribbean origin.

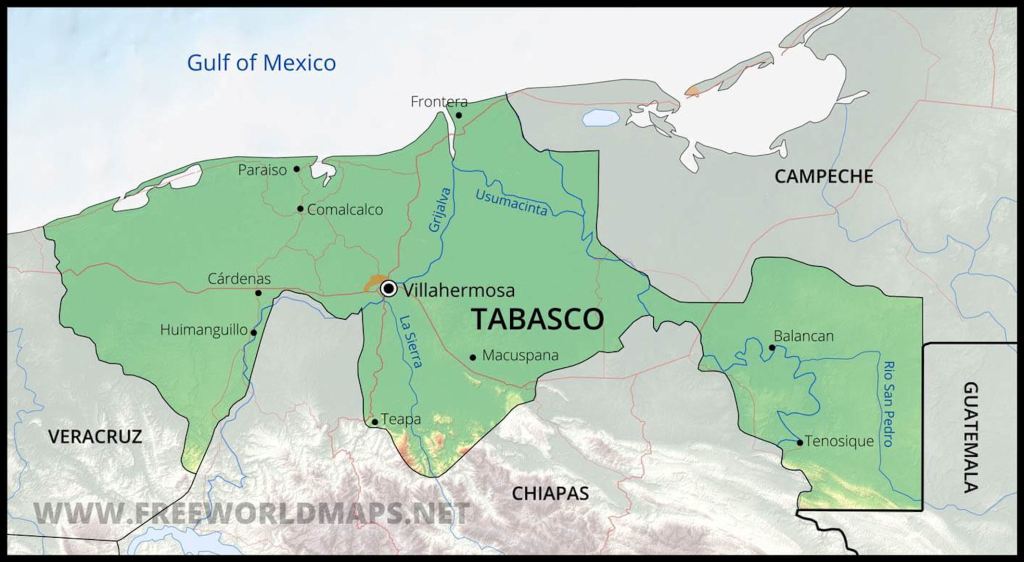

Most branches of the Creek Confederacy can be traced by migration legends and genetics to peoples in southern Veracruz, Tabasco, Chiapas and Campeche. The great rivers of Tabasco were “interstate highways,” which inter-connected much of the Maya world to the Gulf of Mexico.

Tabasco’s Tidal Marshes

Geography identical to Tabasco

The South Atlantic Coast from Charleston, SC southward to St. Mary’s, GA is identical to the coastal region of Tabasco State, Mexico. The first time that I beheld the Tabasco Tidal Marshes I was astounded at the similarity. I was born near the Georgia Coast.

However, the tidal marshes at the mouth of the Usumacinto River in Tabasco dwarf those of the South Atlantic Coast. They are more the scale of Lake Okeechobee, Florida or perhaps the Everglades . . . but with vegetation like the South Atlantic Coast.

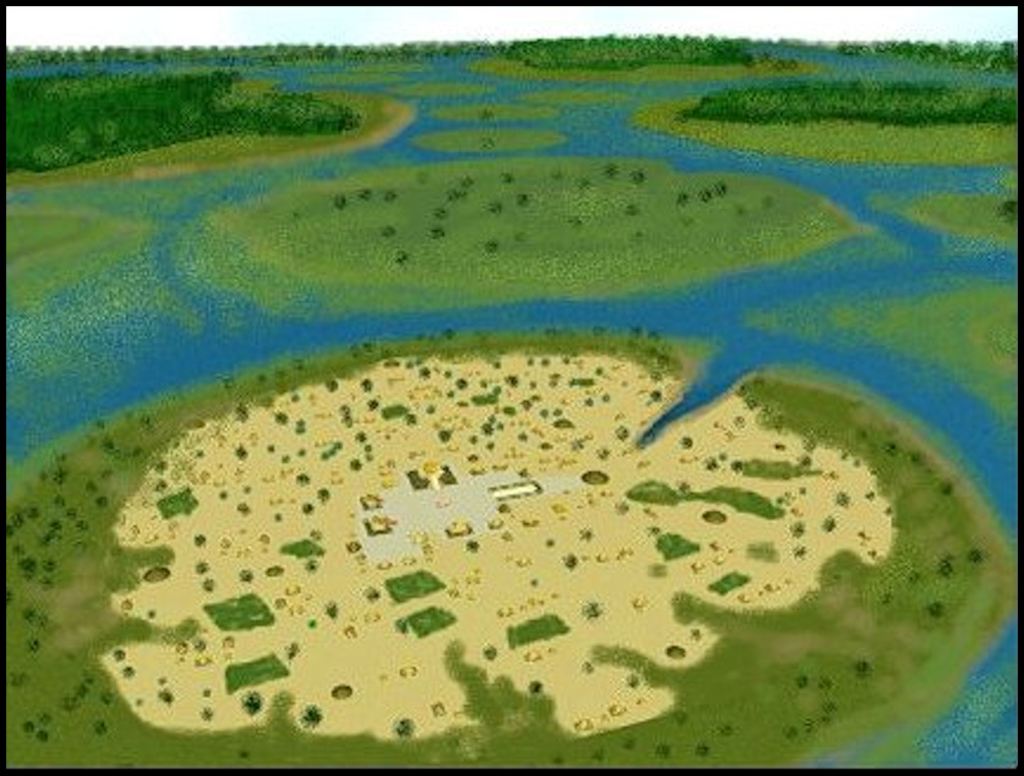

The ancestors of the Chontal Mayas first settled on small roundish islands in the Tabasco Marshes. Their architecture and earthworks were almost identical to those erected by the Creek Indians in Georgia and South Carolina in the centuries immediately before European Contact. . No stone was available in coastal Tabasco for masonry style architecture. The Chontal Maya initially dug simple channels to enable their freight canoes to directly access villages (on upper right of drawing). They also protected the canoes during tidal surges. These evolved into long canals leading away from ocean estuaries and rivers that had round cul-de-sacs at their termination point, so the boats could easily turn around. I visited a Chontal port on the Gulf Coast of Campeche, named Uaymil, in which the canal was over two kilometers (1.3 miles) long,

Chontal Mayas

Mexican anthropologists currently believe that the ancestors of the Chontal Mayas were NOT ethnic Mayas, but migrated to Mexico in the Formative Period from southern Central America or northern South America. This is also the case for the Itza Mayas. Over time, these “Western Mayas” adopted many Maya, Soque and Totonac words into their languages to the extent that their languages are considered Mesoamerican. Perhaps the Chontal Mayas settled on the small islands in the marshes, because no one lived there.

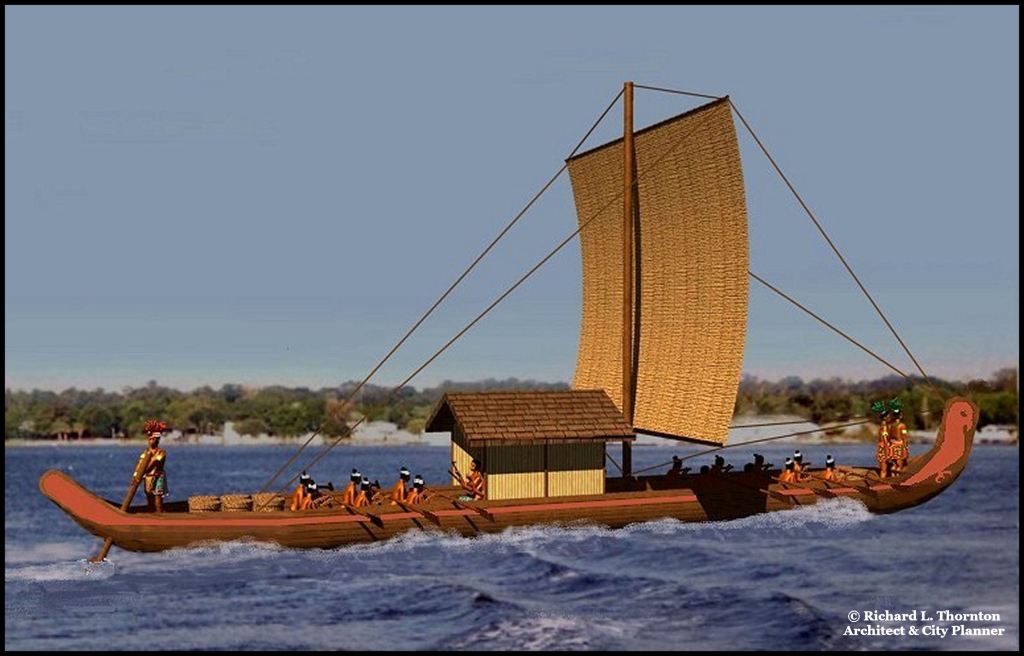

Over time, they became increasingly adapted to a maritime lifestyle that intermeshed with very sophisticated agriculture. Since ethnic Mayas typically did not want to live within 32 km (20 miles) of the ocean, because of hurricanes, the Chotal Mayas quickly became the coastal and riverine traders, who interconnected independent city states . . . even in time of war.

By the Classic Period (c. 200 AD) the Chontal were constructing plank-built cargo boats, which could haul bulk commodities long distances over the ocean. By the Late Classic Period (c. 800-900 AD), they were building sailing ships, which quite similar in size and construction to Scandinavian långbåt vessels. During the Post-Classic Period Chontal Maya merchants became the princes and elite of the Mesoamerican world, due to their wealth and political influence.

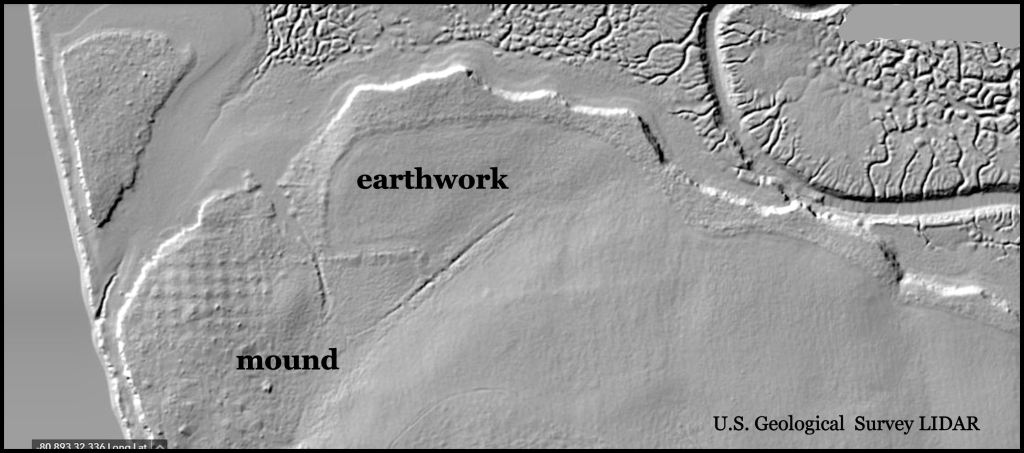

The LIDAR scans

LIDAR scans record the topography of both ancient and contemporary alterations to the natural landscape.

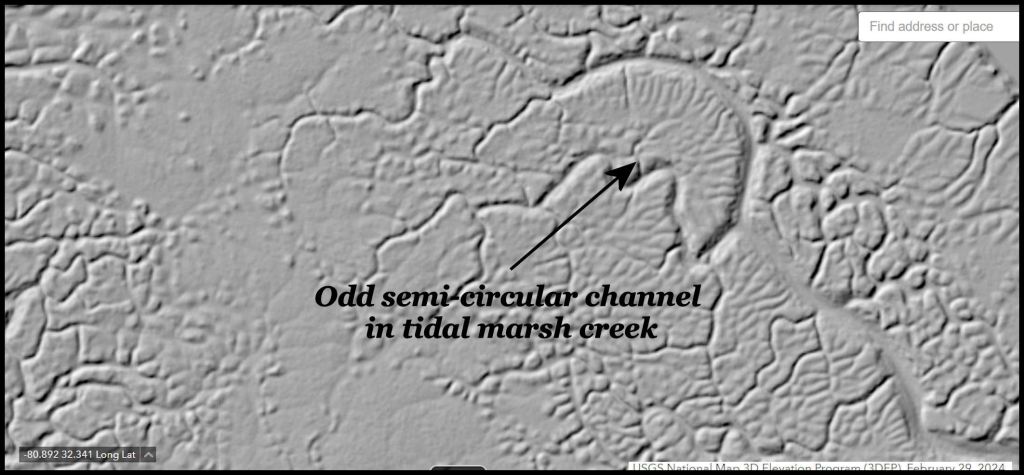

It seems odd that Mother Nature would create a perfect semi-circular bypass for a tidal creek. It is possible that there was a circular burial mound, composed of packed clay, which caused the water to pass the structure.

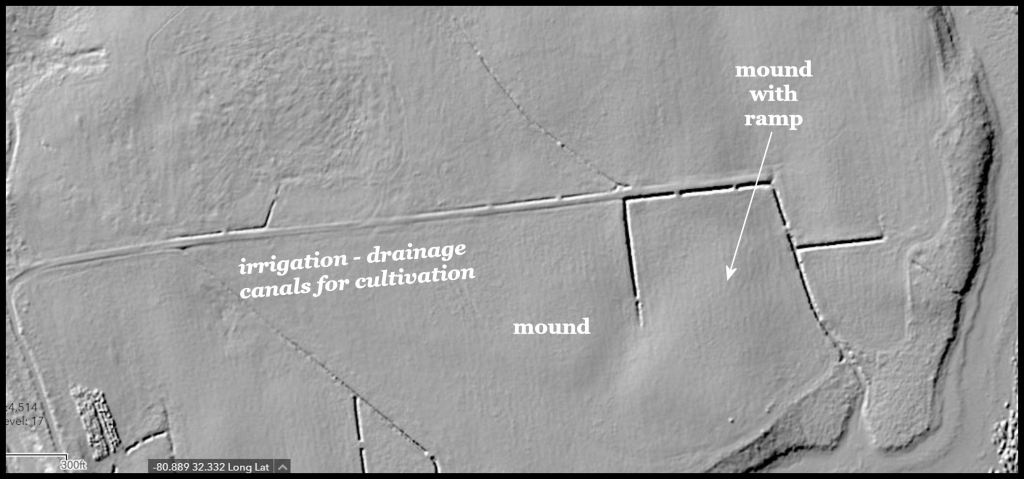

High resolution LIDAR revealed major drainage canals of varying age on the the small island. Less obvious, but still visible are the faint lines of irrigation channels for rice cultivation in the past and some rectangular mounds with ramps . . . of unknown age and cultural affiliation.

Satellite Imagery suggest a Spanish fort

At first, I thought the V-shaped structure was some sort of harbor that had silted in. Then I noticed that the exposed oyster shell foundations were the exact shape of a 16th century bastion. Overall, the physical features were similar the footprint of Fort San Marcos I on Parris Island and the first fort built by the Spanish at Cebo in the Philippine Islands. Could be?

Anything beyond the speculations that I made from LIDAR and satellite imagery will require on-site visits by archaeologists. Given that this island is adjacent to a major Native American archaeological zone, the probability of finding Native American artifacts on this island is 100%. Whether or not there are also vestiges of a Chontal Maya port or a European fortification will just have to wait, until archaeologists survey the island and do test excavations.